It's the soul of Single Malt whisky. Chemistry-wise the most pure structure of them all. It brings depth, complexity, and a smooth, balanced finish. Rich, malty, with subtle notes of toffee and fruit. Simple, yet unforgettable.

Corn is bourbon. It’s the grain that defines the style—smooth, approachable, and deeply tied to bourbon’s roots. With its natural sweetness, corn forms the foundation of this iconic whiskey. It's presence makes every sip easy yet rich. In bourbon, corn is king.

Rye is bold and resilient. Spicy, peppery, dry. It’s a favorite for those who want more than the smoothness of corn or the maltiness of barley. Bold & spicy. That’s the power of rye.

Corn is bourbon. It’s the grain that defines the style—smooth, approachable, and deeply tied to bourbon’s roots. With its natural sweetness, corn forms the foundation of this iconic whiskey. It's presence makes every sip easy yet rich. In bourbon, corn is king.

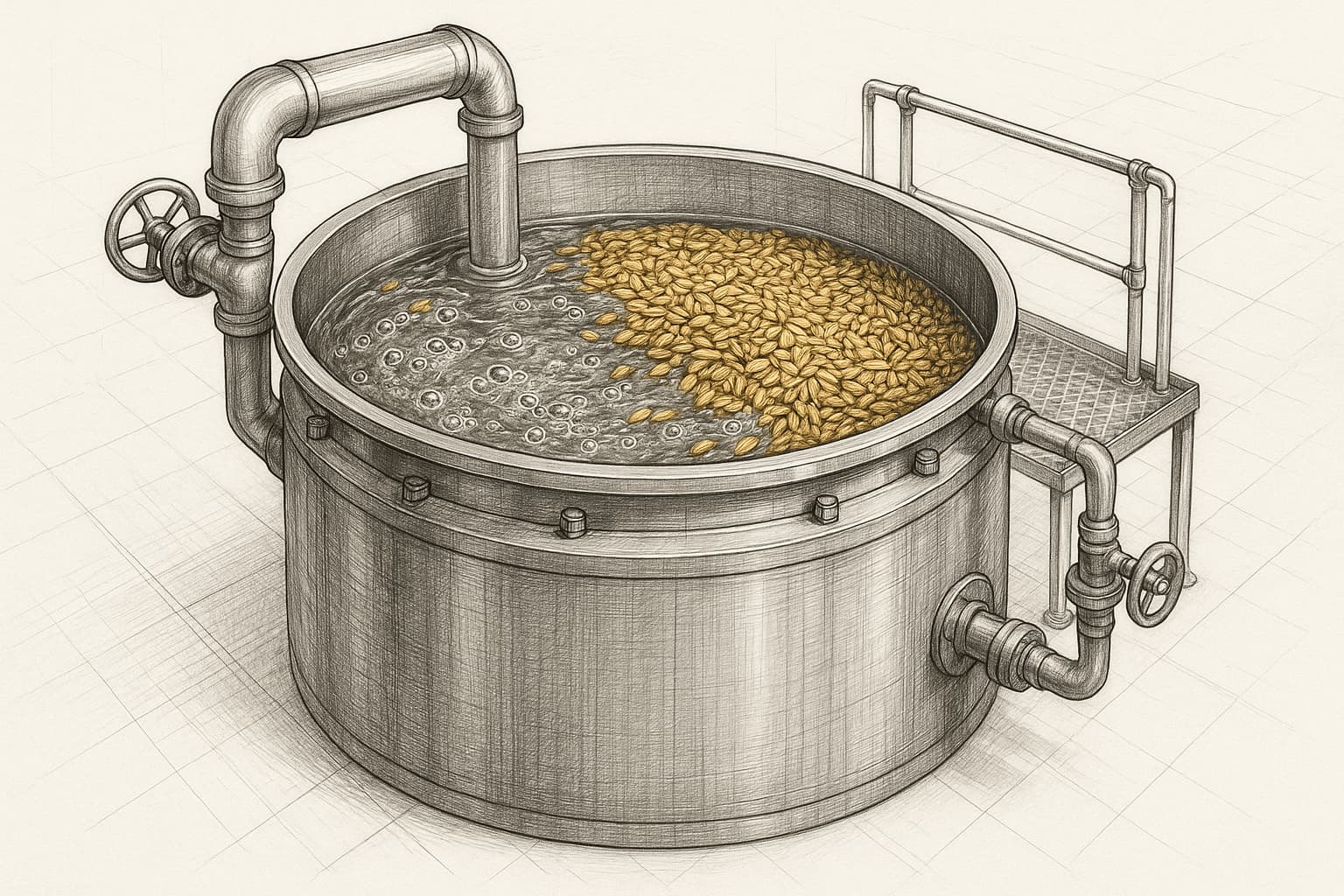

Immersing grain in water, usually in large tanks, stimulates the later process of germination. Malters alternate between submerged in water and periods of air rest, to ensure the perfect levels of moisture. Submerging in water will raise the moisture levels from 10% to a whopping 45%. This activates the enzymes which are needed to convert the starches into sugars later on.

The water temperature and quality are carefully monitored by the distillery, since both impact enzyme activity and later on the whisky characteristics. Once the barley has absorbed enough water and it shows signs of sprouting, it’s ready to be moved to the germination stage.

After a long time in the water, the grain now gets to rest. From now on, the grain is called malt. Spread to a 30cm layer on an air vented plateaus in a darkened chaimber. To prevent the malt from sticking to each other and suffocating, the malt must be shovelled frequently. Specially trained employees of the distillery, called malt men, shovel the malt every 8 hours with wooden rakes and shovels.

The Malt men will continue germination until the white structure inside the malt, called rootlets, are grown to between 2 à 3 millimeter. It usually takes up from four to six days. With each shove fresh air is pushed in the malt layers, thereby dropping the temperature. A very useful side effect, since germination releases energy and thus heat. Too much heat and the malt would start spontaneous combustion, to be prevented for obvious reasons.

Eventhough germination can take up to more than a week, it shows change after 24 hours already. A malt kernel slowly cracks open to make room for the growing rootlet. It allows more water and air to reach the enzymes as well, resulting in a more rich kernel.

In modern time, economics and practicality forced the art of Malt men to make place for large scale industrial shovelling. As often with innovation, it improves what it replaces. Industrial malting results in better control during germination and overall more consistent grains.

Only a handful of distilleries are still loyal to the traditional way of working. The Balvenie in the Highlands, Highland Park on Orkney island and Bowmore & Laphroaigh on the Islay.

Essential to a good whisky, is knowing when to stop the germination process. Wait too long and it will cause the rootlets to become too big or welcomes nasty reactions that will spoil the malt. When the rootlets are roughly at similar length as the malt itself, germination is stopped by placing the malt into the malt oven, called a kiln. The floor of the kiln has many tiny holes in it, through which heat from the fire beneath dries the malt. The goal is to stop germination by reducing the moisture levels to approximately 4%. Now it's stable for storing and milling. Because the heat is from direct fire it can transfer certain characterisitics to the malt via the smoke.

At first, the malt kiln is heated to a controlled 50°C to drive off any surface moisture without damaging the grain's enzymes. As drying progresses, the temperature is increased to between 80°C - 105°C. The malt men has a choice to make: higher temperatures make a more malty-flavoured whisky.

The way malted barley is dried is one of the most critical steps in defining the character of a whisky. This stage determines whether the final spirit leans toward a clean, cereal-forward profile or carries the deep smokiness for which many Scotch whiskies are famous.

There are two primary approaches:

The level of smokiness—known as “peatiness”—is carefully managed. Distillers can adjust both the duration of smoke exposure and the type of peat used, fine-tuning the intensity and flavor spectrum of the final whisky.

Together, soaking, germination, and drying transform raw barley into malt—the foundation of every whisky. Each step builds on the last: water awakens the grain, germination unlocks its sugars, and drying locks in character, whether clean or smoky. With the malt complete, the whisky-making journey moves from grain to spirit.